Episode 8: Eden to Ashes

In this episode, we venture into the tragic story of the 1902 volcanic eruption of Mount Pelée on the island of Martinique. Consul, Thomas Prentis and his family were among the 30,000 victims of this natural disaster.

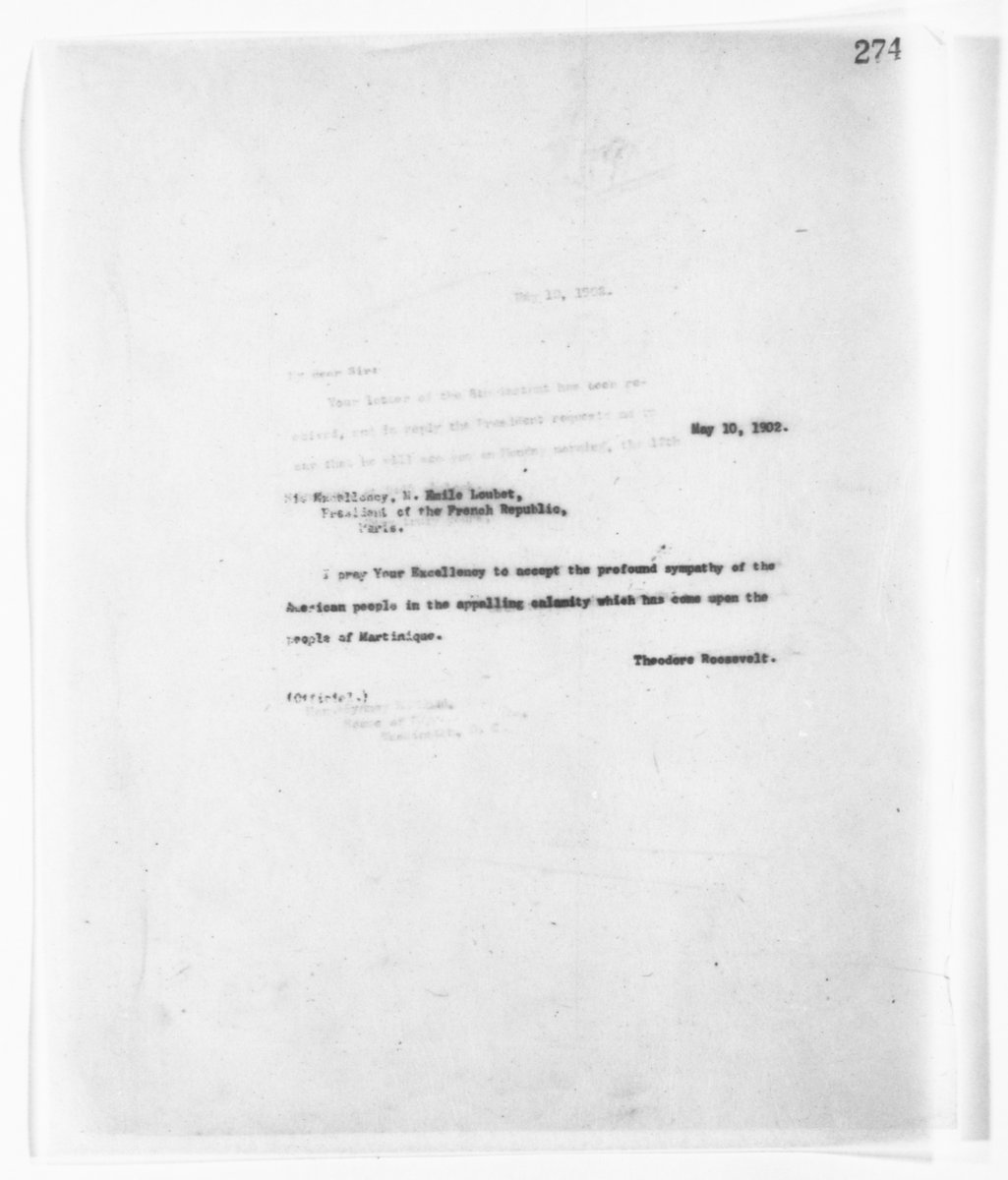

We will discuss the eruption itself, and the diplomatic consequences for Martinique.

Further Reading

Church, Christopher M. Paradise Destroyed: Catastrophe and Citizenship in the French Caribbean. (University of Nebraska Press, 2017).

Johnson, Wally R. Roars from the Mountain: Colonial Management of the 1951 Volcanic Disaster at Mount Lamington. (ANU Press, 2020).

Morgan, Peter. Fire Mountain: How One Man Survived the World’s Worst Volcanic Disaster (Bloomsbury, 2003).

Scarth, Alwyn. La Catastrophe: The Eruption of Mount Pelée, the Worst Volcanic Eruption of the Twentieth Century. (Oxford University Press, 2002).

Credits

Producer: Abby Mullen, Megan Brett, and Brenna Reilley

Fact-checking: Deepthi Murali

Voice actors: Scott Moore, Nate Sleeter, Cindy Garland, and Maggie

Music: Andrew Cote

Again, remember to follow us on social media so you can see volcanic eruptions like Mount Pelee, and thanks for listening.

ABBY MULLEN: Before we get going with today’s show, a warning. There are some pretty scary parts to our stories today. So if you’re listening with kids around, you might want to put headphones on. All right, here’s the show.

SAN FRANCISCO CALL:

Destruction is again threatened by Mont Pelee, the volcano having resumed an activity even greater than that exhibited when St Pierre was wiped out of existence. For twenty-four hours the volcano has been in constant eruption and explosions have been frequent…

Last night was one of terror and wild alarm here. The earth seemed to have lost its foundations. Up through the crater of Mont Pelee poured a storm of death….

At this time nothing definite is known of conditions further to the north. Smoke fills the air, darkening the sky. Ashes are falling steadily. When the heavens are filled with lightning, as frequently happens, it can be seen that Mont Pelee has not ceased to throw out a great column of lava and stones. There has been a perfect calm in the air, yet the waters of the Caribbean are lashed to a fury, indicating that the same forces that cause the volcano to labor are working tremendous changes at the bottom of the sea. Words are inadequate to describe the actual conditions. Disaster is expected at any moment, and in the harbor every ship has steam up and is ready to slip cable and speed away.

Beset by imminent and terrible danger, a party of officers from the Cincinnati and Potomac went ashore at St. Pierre yesterday and brought away the body of Thomas D. Prentis, the American Consul.

Advised to forsake their burden and save themselves, the men who were carrying the body refused to do so. On they stumbled, through an atmosphere each second growing darker and more stifling. Their ears were deafened by the crashes that came from Mont Pelee. In the roadstead, the British cruiser Indefatigable was putting to sea, sounding her siren, which most of the time was silenced by the great noise of the mountain…

Finally the brave men were forced to rest their burden at the water’s edge, while they made all speed for the Potomac. They were barely in time. As the steamship got well under way, another flood of fire poured down from Pelee and a broad stream of lava ran into the sea, while out of the sky rained a storm of rocks and ashes.

The San Francisco Call. (San Francisco [Calif.]), 21 May 1902. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85066387/1902-05-21/ed-1/seq-1/

MULLEN: When the San Francisco Call published this report on May 21, 1902, the body of Thomas Prentis, American consul in St. Pierre, Martinique, was just one of almost 30,000 bodies that lay in the town of St. Pierre. This eruption of Mont Pelee was the deadliest volcanic eruption of the twentieth century. The main character in our story today isn’t a consul, but rather a natural force: a volcano. The consuls in Martinique are just secondary players.

MULLEN: I’m Abby Mullen, and this is Consolation Prize, a podcast about the history of the United States in the world through the eyes of its consuls. Before we take a closer look at the eruption of Mount Pelee, and the human decisions that made it so very tragic, I wanted to let you know that Consolation Prize is all over social media. We have Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter, and we’d love to hear from you on those platforms. We post a lot of extra stuff about consular history there, so you’re missing out if you don’t follow us on one of our platforms! For instance, on our social media today and for this episode, we’re posting a lot of footage of volcanic eruptions that are very similar to Mount Pelee. So if you want to know what this sort of disaster looks like, follow us and find out.

MULLEN: Now we started kind of at the end of this sad story. So you already know what happened to the consul. But what we don’t know yet is why he was there to begin with. So let’s back up a little.

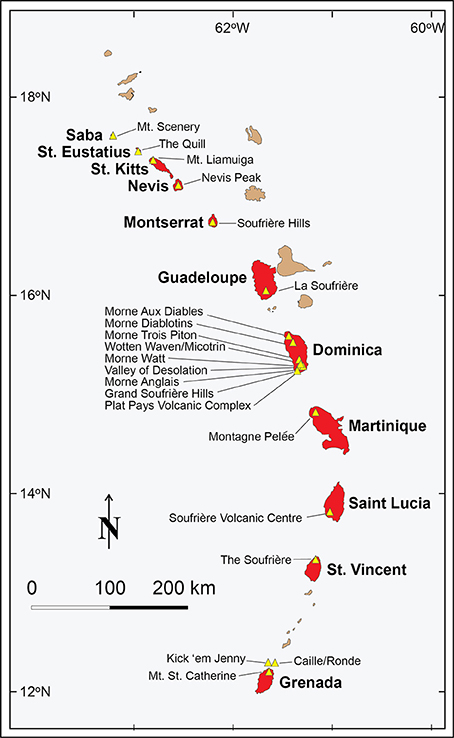

MULLEN: First of all, let’s talk about where Martinique is. It’s in the Lesser Antilles–the Caribbean. It’s one of the islands that forms a vertical line up from South America, close to the Atlantic Ocean. So one side of the island faces the Caribbean Sea, and the other side faces the Atlantic Ocean. It’s a lush and beautiful tropical island, where the soil is fertile and crops like sugar grow exceedingly well.

MULLEN: In 1902, Martinique belonged to the French empire as a colony. And so all the direct connections the United States had had to Martinique up until then had been through consuls, rather than through an ambassador or minister who was in Paris. And this consular relationship was very long-standing—in fact, the first consul to Martinique was appointed, just like James Maury from Episode 2, before the consular service even existed officially. His name was Fulwar Skipwith, and he was appointed in 1790.

MULLEN: Martinique wasn’t a big island, but it had one thing going for it that the United States really wanted:

CHRISTOPHER CHURCH: Sugar. The world had, by the 19th century developed an incredibly strong sweet tooth, and not just as we usually think of it is in terms of sweetening desserts in the like, but it actually had been incorporated into vast swaths of the world’s diet. And so virtually all food products today, but even by the 19th century, contained some level of profit Sugar. And in fact, between 1890 and 1930, US per capita consumption of sugar had nearly doubled. And so this is the same period where the United States was starting to try to build its own sugar empire. Most United States sugar had been imported. And so Martinique and Guadeloupe, really the French Caribbean generally had been trading sugar with the United States going back to the period of imperialism and slavery.

MULLEN: That’s Christopher Church, a historian of disasters and social movements. He told us that in 1902 Martinique occupied an unusual place in the French Empire, as colonies go.

CHURCH: By 1902, the people in the French Caribbean, both white and black, were French citizens. So they had voting rights in the Third Republic, they had locally elected officials. They even had representation in the national French legislature, but they were still overseen by an appointed governor and colonial administration. So the closest analogue I would say today in the United States would be Puerto Rico, citizens of the nation, but not yet able to fully participate in that nation. And Martinique and Guadeloupe though were also as parts of that older Empire, the sites of French slavery. So they were areas of intense racial strife, strongly shaped by the legacy of colonial exploitation. But it’s also the place where the people there push back and really tried to hold the republican values of liberty, equality and fraternity, trying to make them true.

MULLEN: By the end of the nineteenth century, Martinique had even more potential in the eyes of many Americans because it could serve as a part of a pipeline toward what would become the Panama Canal.

MULLEN: So the consul in Martinique was pretty important. The consul in 1902 was, as you know, Thomas Prentis. He was a career consul, with many powerful friends in the government. Martinique was not his first post. He had served in the Seychelles and in Rouen before this. For some reason, in 1900, he decided he wanted to leave Rouen, so he asked his friend Henry Cabot Lodge to help him get a new post in Batavia, which is modern-day Jakarta, Indonesia. Lodge got the Secretary of State to agree to the appointment, so Prentis and his adult son left for Batavia. After they left, Lodge was informed that the president had actually appointed someone else to the post.

MULLEN: Poor Lodge had to write to Prentis to tell him that he didn’t get the job after all–and after he’d traveled all that way. He tried to cast the news in the best possible light. He had been able to get Prentis a different post, in Martinique, which was probably more lucrative than Batavia anyway. And just think of how much easier it would be for Prentis’s wife Clara and his two daughters to get to Martinique rather than traveling all the way to Batavia!

MULLEN: So Prentis and his son boarded a ship and headed back home. As the ship steamed back to the United States, Prentis could probably see Krakatoa in the distance in the Sunda Strait. And then he was off to take up his new post in St. Pierre, Martinique, the “Paris of the Antilles.”

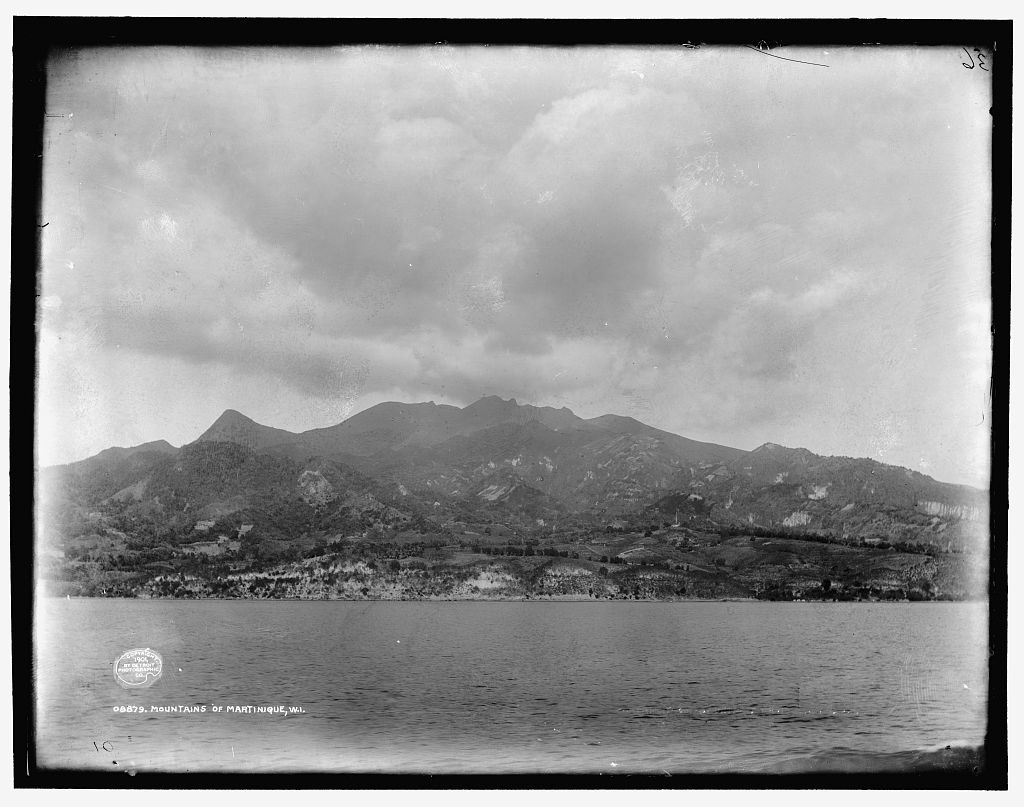

MULLEN: The paradise that Prentis was going to was indeed beautiful. But its beauty rested on top of a terrifying foundation. The most striking physical feature of the island was a mountain over 4000 feet tall, named Mount Pelée. Charlie Mandeville, the volcano hazards Program Coordinator at the US Geological Survey, told us more about the geology of the area.

CHARLIE MANDEVILLE: Mount Pelée is one of the Lesser Antilles chain volcanoes. All of the islands in the Lesser Antilles chain, they’re really, the amalgamated portions of what started as submarine volcanoes that eventually broke, the sea surface and emerged as islands. And, or, amalgamated volcanoes that, you know, combined to form a somewhat larger Island because some of the Lesser Antilles islands have two or three volcanoes on them. And many of these, they’ve been active volcanic centers for a million years, or maybe 500,000 years.

MULLEN: People on Martinique were fully aware that this volcano could be a threat–but it didn’t seem very threatening. Its last eruption had been in 1851, and even that one hadn’t been particularly big or terrible. People even thought that that eruption in 1851 was the sort of last gasp of an old and dying volcano. So when the volcano started to rumble and make noises in the spring of 1902, people didn’t realize the danger they were in. It did seem like something was going on, though. Clara Prentis wrote to her sister on the Morning of Saturday, May 3rd, 1902:

“My Dear Sister, This morning the whole population of the city is on the alert, and every eye is directed toward Mount Pelée, an extinct volcano. Everybody is afraid that the volcano has taken into its heart to burst forth and destroy the whole island. Fifty years ago Mount Pelée burst forth with terrific force and destroyed everything for a radius of several miles. For several days the mountain has been bursting forth, and immense quantities of lava are flowing down the side of the mountain. All the inhabitants are going up to see it.”

Ernest Jr. Zebrowski. The Last Days of St. Pierre: The Volcanic Disaster That Claimed Thirty Thousand Lives. (Rutgers University Press, 2002).

MANDEVILLE: They did actually notice that they had this rotten egg smell of sulfur gases present, wafting down, the slopes of Mont Pelee. They also started seeing changes in the local groundwater wells that they were accessing for drinking water. Sometimes a well would go dry, for no apparent reason when it had water in it last week. Other times, they’d see the Rivière Blanche, the White River, dry up for a week and then be coming down and torrents two days later without any significant change in rain. So where did all that water come from? And the main kind of gases that are dissolved in magmas are mainly water, carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, maybe a little bit of hydrogen sulfide, and maybe a little bit of hydrogen chloride. So those are the main things that are dissolved in magma. And the things that have the least solubility like C02, and some of the sulfur gases, they’re going to come out first, as the magma ascends to the surface. Whereas the gases that have high solubilities, like water and chlorine, they’ll come out last when the magma is literally at the surface.

Mountains of Martinique, W.I. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

MANDEVILLE: The people may have also noticed that maybe their drinking water tasted a little bit acidic. And the reason that’s happening is because gases coming out of the magma like SO2 and CO2 and hydrogen chloride, they’re literally acidifying the local groundwater which the people are drinking. So changes in just the taste of your groundwater is telling you that something is happening in the subsurface. And then you know, there’s accounts of all the animals being scared away from the summit of the volcano on Mount Pelée, you know, during the April to May timeframe before May 8. And that’s naturally going to happen because the earthquakes are being felt by the local animals. The changes in groundwater are being felt by the local animals. The acidification of the groundwater is being sensed by the local animals. And they’re migrating downslope to get away from it.

“The city is covered with ashes, and clouds of smoke have been over our heads for the past five days. The smell of sulphur is so strong that horses on the street stop and snort, and some of them are obliged to give up, drop in their harness, and die from suffocation. Many of the people are obliged to wear wet handkerchiefs over their faces to protect them from the strong fumes of sulphur. My husband assures me that there is no immediate danger, and when there is the least particle of danger we will leave the place. There is an American schooner, the E.J. Morse, in the harbor, and it will remain here for at least two weeks. If the volcano becomes very bad we shall embark at once and go out to sea.”

Clara Prentis to Miss Alice Fry. Ernest Jr. Zebrowski. The Last Days of St. Pierre: The Volcanic Disaster That Claimed Thirty Thousand Lives. (Rutgers University Press, 2002).

MULLEN: Despite all these clear warning signs that something was going to happen, very few people actually left St. Pierre or the island. In part, this was because the only scientist in the area said that it was safe. He had no training in volcanology, which wasn’t even really a thing yet—he was basically a high school science teacher. But his word convinced the local officials that everything was going to be ok, if people just sheltered in the right place.

CHURCH: Leading up to the eruptions, officials thinking of this main risk of lava, they positioned St. Pierre as a safe haven. This was actually a myth that was deeply bound up in French colonialism, because the French culture of colonialism was that they were bringing civilization to otherwise harsh environments. And so since St. Pierre was the Paris of the Lesser Antilles, or the little Paris of the Antilles, it was seen as this kind of European safeguard or bulwark against a dangerous environment around, and so the thinking was that if everyone sheltered in the city, if everyone got out of the countryside and evacuated, then they would be safe.

CHURCH: There are about just shy of 30,000 people who had been collected from all over the countryside. In fact, the governor Louis Mouttet even organized military details to patrol the roads to force people into the city and made a point of staying there himself to prove to everyone this is the safe location.

MULLEN: In fact, the awakening volcano became sort of a scientific and social curiosity.

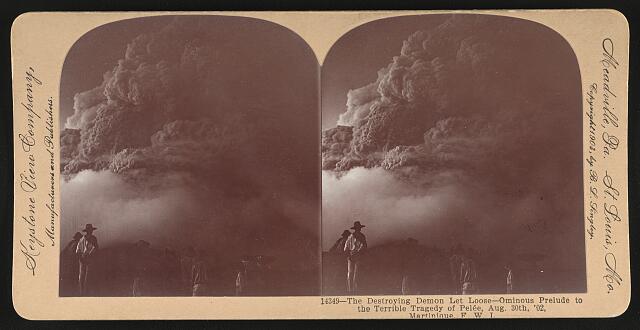

CHURCH: They actually organize picnics to go see the gases coming out of the top, up at the base of the mountain. For about three weeks, this kind of fuming went on from I think was about April 23 till May 8.

MULLEN: The mountain really began serious signs of eruption early in May of 1902. Again, despite these indications, including small lava flows and release of significant smoke and ash, very few people left the city of St. Pierre. And then, on May 8, the crisis. In just a few minutes, Mount Pelée transformed from a curiosity into a catastrophe.

MANDEVILLE: One of the things that we know happened, we had something called a nuee ardente, a glowing cloud, essentially emitted from the summit of the volcano. And these glowing clouds are really hot avalanches. And the hot avalanche is composed of small fragments of glass that are like less than two millimeters in size, to existing rock fragments that comprise any rock that was present as part of the volcano that’s being pulverized. And a mixture of hot gases that are literally coming out of the magma for the first time as the magma reaches the surface. And you have to keep in mind that these gases and small bits of magma, when they were down in the crust, say at a depth of two or three kilometers, they were probably at temperatures of 800 to 950 degrees centigrade. And that’s essentially 1600 to 1800 degrees Fahrenheit. So it’s literally glowing bright orange. And this material is all coming down the flank of the volcano as the hot avalanche, and it might be three kilometers to the top of it. So that’s how big the cloud is.

MANDEVILLE: And the cloud at its base has some other denser fragments, jostling and breaking and releasing gas as they actually tumble downslope and get reduced in size. All of this is moving at a speed of 100 miles an hour.

MANDEVILLE: The summit of Mont Pelée was seven kilometers from the town of St. Pierre. And anything moving at 100 miles an hour is going to be on the city in 2.7 minutes. And so, literally St. Pierre is obliterated by what we refer to as a pyroclastic flow, and an associated ash cloud surge. And I know those are mouthfuls, but it’s essentially, the magma that is breaking apart, releasing high-temperature gases, releasing volcanic ash, because it’s literally the magma that’s blowing apart, and being reduced in size to things as small as something that fits on the head of a pin, to things the size of television sets, refrigerators and dining room tables. And it’s all hurtling down the flank of the mountain at 100 miles an hour. And because the gases that are coming out of the magma, they’re still nearly 500 degrees centigrade, essentially, when you as a human get exposed to that your lungs are traumatized in seconds, and you die from lung trauma. And then you’re burned on top of it. So most of the inhabitants of St. Pierre were actually succumbed to lung trauma, because in seconds, they breathed in that very high-temperature gases. And they suffocated. And then they were buried.

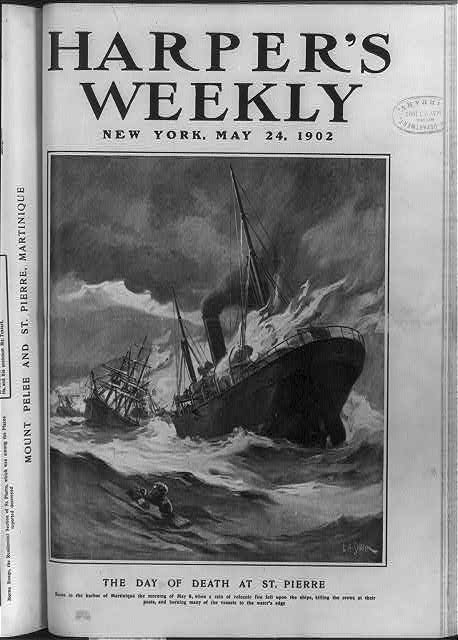

MULLEN: The people in the city never had a chance. There were ships in the harbor that could have helped people escape. And a few did. But the ships were in trouble too.

MANDEVILLE: Most of them were actually capsized instead of fire. And we know about these kinds of things because there were several ships in the Sunda Straits following the eruption or during the eruption of Krakatau in 1883. And they tell us what it’s like to see a pyroclastic flow or an ash cloud surge rushing past you, setting your sails on fire and covering your deck with a foot of you know, volcanic ash, and hot smoldering pumices and glowing pumices. And so most of the ships in the harbor at St. Pierre were actually overturned, capsized, and set ablaze. And very few of them actually survive. And the other thing that we know definitely happens because we’ve actually caught it on video following some of the Montserrat eruptions of Soufriere Hills volcano, is this pyroclastic flow, this hot, glowing cloud, when it reaches the air-sea interface, it actually can skip because it’s moving at 100 miles an hour. It’s moving along the surface of the ocean and incinerating everything in its path.

MULLEN: Less than 10 minutes after the pyroclastic flow descended upon the city of St. Pierre, there was nothing left of the city. The people who lived there, the people who were visiting, the people who had sheltered there after evacuating from their homes and farms on the side of the mountain: they were all dead. Black, white, wealthy, destitute, men, women, children, it didn’t matter. There’s no way to get an exact count of the death toll, but the best estimates are between 28,000 and 30,000 people were just…gone.

MULLEN: Among the dead were Consul Thomas Prentis, his wife Clara, and their two daughters, along with the vice consul, Amedee Testart and his family. Testart wasn’t killed immediately: he escaped from the land and made it onto one of the few boats that didn’t sink, but he died a little while later from exhaustion.

MULLEN: Historian Alwyn Scarth wrote that there were maybe 2 people who were in the direct path of the ash surge who survived. One of them became famous for a time. He survived because the room he was in was relatively sealed off from the outside world, and he had the presence of mind to cover his face before the gases and superheated dust could suffocate him. Where was he? In prison. After searchers discovered him a few days after the initial eruption, he gained some fame and he even traveled for a while with an American circus as a curiosity.

MULLEN: Some people were far enough away to watch as the disaster unfolded. One observer was a little girl, who was eventually rescued by a French cruiser.

“I ran as hard as I could to the beach, and saw my brother’s boat with sail set close to the stone wharf where he always kept it. I jumped in it, and just as I did so I saw him run down toward me. But he was too late, and I heard him scream as the stream first touched, and then swallowed him.

I cut the rope that held the boat and went to an old cave about a quarter of a mile away, where we girls used to play pirates, but before I got there I looked back and the whole side of the mountain which was near the town seemed to open and boil down on the screaming thousands, I was burned a good deal by stones and ashes that came flying about the boat, but I got into the cave.”

William A. Garesché, Complete Story of the Martinique and St. Vincent Horrors… (Monarch Book Company, 1902), 36.

MULLEN: The eruptions kept going for many weeks after the first blast on May 8, but the survivors on the island needed help immediately. Rescue and relief efforts got underway as soon as the tragedy was known, both in France and elsewhere in the world.

CHURCH: It gets cast as largely a national emergency. And so most of the aid, the vast majority of it comes from mainland France, with some of it coming from Francophone colonies. The French ended up organizing large fundraising campaigns to get donations from everyday people. They also pass a bunch of legislative measures to appropriate special budgets for Martinique, to help pay stipends to people and to help rebuild. Although there’s a whole debate about where to rebuild and how.

CHURCH: They saw this as an attack on the very notions of French civilization abroad, and really the civilizing mission, their whole ethos for colonialism. If the French couldn’t French civilization couldn’t protect against this, what good is French civilization. People really soul searching about what this meant for the lie, they essentially been telling themselves that they’re bringing, the cornucopia of civilization to all of the world’s people, and they’re really doing good work. And yet, in literally minutes, as you pointed out, 30,000 people are dead precisely because they were sheltering in the structures that the French had built as a bulwark against the environment.

MULLEN: The United States also wanted to help. They had lost one of their own, after all–and perhaps more importantly, they needed Martinique to be back up and running if their plans for Caribbean dominance were going to happen. In a little over a month, a new consul, John Franklin Jewell, was dispatched to the island, where presumably his main job would be to help with the relief effort. One former consul wrote to beg Americans to contribute to the relief effort:

William A. Garesche: “Martinique prior to its destruction was the nearest approach to any idea we could have of the Garden of Eden. Alas! Like all things earthly, its beauty was evanescent, it has passed away, and while I sigh for its destruction I am proud of the ready sympathy our great and grand country has shown in the hour of distress, I know that generous hearts of my countrymen will reap full meed of gratitude from that poor impoverished people.”

MULLEN: Private citizens from the United State contributed to the cause. For instance, Levi Strauss, the jeans guy, gave $500. But the US government also got involved.

CHURCH: Money from the United States was really a drop in the bucket. But even though monetarily it didn’t amount, it had a huge significance in terms of the chatter in debates, mainly in the French press, but even in official documentation about what to do about it. So Roosevelt got Congress to give about originally was going to be a half a million dollars. And then it gets pared-down to like, it’s $200,000. But then, the reports in the French archive suggest that the majority of that never even got distributed to France, most of it sat in US coffers, and then got re-diverted to the Philippines two years later.

MULLEN: The French metropolitan authorities weren’t fully convinced that the United States just wanted to help. They suspected an ulterior motive.

CHURCH: From the French perspective, it wasn’t seen as altruism. The French are incredibly wary. In fact, in the words of the French ambassador to Washington DC, they argued that Roosevelt’s attempt to help was emblematic of, “America’s hegemonic spirit with respect to all dependencies in the new world.” In other words, they saw this as a direct way of the Americans flexing their muscles in the Caribbean, so to speak. This was also the height of American yellow journalism. And so the French were very angry that journalists kept saying that Martinique would be better under American control. In fact, American journalists repeatedly pointed to Haiti, of what would happen if Martinique was abandoned by the French and what, you know, they saw as the ultimate end point of French control of Martinique, as a way of saying it, but if you came to America, you’d be so much better off.

MULLEN: We don’t have a lot of hard and fast evidence that the United States government was explicitly trying to peel Martinique away from the French empire. But this disaster certainly happened at a time when the US empire was growing larger and larger. And with the construction of the Panama Canal underway, the United States was looking for ways to increase its influence in the Caribbean.

CHURCH: The French did have a reason to be worried, the United States does occupy Haiti in 1915, and they stay there for nearly 20 years until 1934 and maintained a military occupation. So that threat of the United States occupying, in this case a former French colony, but if Martinique did become a former French colony, after 1902, I think it was very real.

MULLEN: But there were good reasons that Martinique’s unusual racial and social systems wouldn’t have worked well if the island did become American.

CHURCH: In 1900, Martinique had its first general strike where wage labor workers on plantations and then the sugar refineries, throw down their tools, set fire to some of the cane fields. But what’s interesting is it actually gets resolved by a labor dispute law that had been passed for the mainland, it doesn’t get put down as an insurrection. The American press flat out sees it as an insurrection. And I can only read it as a threat to the Jim Crow status of the United States. That if you actually have black French workers, who are treated as French citizens and the French, and having French black workers go on strike. And black workers who vote for local black officials, in the islands, in America’s own backyard, was seen as an inspiration perhaps to people in the south that would threaten the United States, you know, post-Reconstruction were Jim Crow reinstates white supremacy.

MULLEN: So what happened to Martinique? Well, even while the French government was sending money to the island, it also kind of distanced itself in the years afterward.

CHURCH: In the immediate aftermath, and to me, it’s one of the scandals of the disaster, is people were immediately thinking of, what if we just got rid of the island? And I think this is also where America figures in because they’re like, well, we’ll take it. And that doesn’t come to pass. But there’s definitely a divestment from Martinique. And this is again, where I see the parallels with the more recent debates about Puerto Rico and its state debt and financial problems there. There’s always that colonial logic of, is this colony worth it? That is not at all altruistic. And those debates began in 1902, as the French legislature was debating cutting checks, to help rebuild. And so Martinique and St Pierre never really got rebuilt. So after the eruption completely devastated the city, killed about 30,000 people in a fell swoop, the city did slowly start to grow. So by 1922, there were about 8,000 people living in St. Pierre and the areas around it. But then there was a second eruption in 1929. And never amounted to the full scale devastation of a pyroclastic flow, wiping out those 8,000 inhabitants. They were all evacuated, about 10,000 people at that point were evacuated. But it dashed the hopes. So today, St. Pierre population is just over 4,000. So nowhere, even near what its population was almost 120 years ago.

MULLEN: Despite the initial impulse to just ditch Martinique, eventually the island did become a full department of France, like a state in the United States, and it remains so today.

MULLEN: And what happened to Thomas Prentis, the American consul who was killed? Unlike many thousands of others, whose names and lives are unknown, Prentis’s surviving family was given $5000 in compensation for his death, and his name appears now on the American Foreign Service Association Memorial Plaque. And the US Navy made it their mission not only to honor his life, but also to recover his body. We heard at the beginning about their first attempt, which wasn’t successful. They tried again, and this time they brought along a journalist.

SAN FRANCISCO CALL:

In spite of the threatening aspect of the volcano, it was determined later yesterday to make another attempt to recover the bodies of Mr. Prentis and Mr. Japp, the British consul. By permission I accompanied the searching party, which was divided into two squads. One led by Ensign Miller went to the site of the American consulate, and soon had the body of Mr. Prentis encased in a metallic and hermetically sealed coffin. Six stalwart fellows shouldered the body and started with it for the landing.

In the meantime, another party, led by Lieutenant McCormick of the Potomac, had proceeded to the British consulate, about a half-mile to the north of the American consulate. Fortunately this was in view of the crater of Mont Pelee. Lieutenant McCormick saw a column of smoke and fire belch from the volcano, from the side of which a streak of molten lava flowed.

Directing his men to make all haste back to the Potomac, the lieutenant turned aside to give warning to the party which was carrying the body of the American Consul.

“For God’s sake, boys, get to the boat quick if you would save your lives!” he gasped. “The volcano has exploded and destruction is upon us!”

At that instant there was a crash in the sky, back of which it seemed as though scores of thunderbolts had been forced into one. As it died away, the loud siren of the Indefatigable, which was in the roadstead, screamed a warning. The British cruiser almost immediately put out to sea at top speed. Without cessation the whistle of the Potomac was blowing. There was another rumble and the sky was filled with lightning. Then, as I looked backward, Mont Pelee cast upward a vast column a mile or more high.

Christopher Church

Christopher Church is a cultural historian and digital historian of the French colonial world who specializes in disasters, nationalism and social movements in the 19th and 20th centuries. He employs new methods from data science and the digital humanities to answer age-old questions about the relationship between citizens, the public sphere and the state. His intellectual interests include colonialism, citizenship and environmental history, as well as databases, GIS, scripting and web design.

His first book, Paradise Destroyed: Catastrophe and Citizenship in the French Caribbean (December 2017, University of Nebraska), explores the impact of natural and man-made disasters in the late nineteenth-century French Antilles, where a colonial population-predominately former slaves-possessed French citizenship, looking at the social, economic and political implications of shared citizenship in times of natural catastrophe and civil unrest. He has also written on strike activity and colonial citizenship in the French Caribbean in the French journal Le Mouvement Social, as well as on the relationship between hurricanes, urban development, race and economic collapse in the 1920s Greater Caribbean for the edited volume, Environmental Disaster in the Gulf South: Two Centuries of Catastrophe, Risk, and Resilience (January 2018, LSU Press).

Charles Mandeville

Charles Mandeville, is the Program Coordinator for the USGS Volcano Hazards Program (VHP) at USGS Headquarters in Reston, Virginia. He has been Program Coordinator for the Volcano Hazards Program since Sept. 2012. He was trained as a physical volcanologist and geochemist and has conducted research at the following volcanoes in his career including Krakatau, and Galunggung in Indonesia, Mt. St. Helens in Washington, Crater Lake in Oregon and Augustine volcano in Alaska. His Ph.D. research focused on all aspects of the Krakatau 1883 eruption in Indonesia and involved the study of both onshore and offshore submarine samples from that eruption in order to characterize the erupted material and to delineate the likely cause of lethal tsunamis generated during the eruption that resulted in over 36,000 fatalities.

He now manages the USGS’ s Volcano Hazards Program (VHP) that operates volcano observatories in Hawaii, Alaska, Cascadia, California and Yellowstone, and the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program (in partnership with the US Agency for International Development), and supporting research and assistance projects. He develops the program’s science portfolio and capabilities and strategies and corresponding budget plans. He coordinates USGS volcano monitoring with the efforts of cooperative university and state geological survey partners. He represents the USGS VHP on interagency and international committees and meetings and advocates the importance of national volcano monitoring to members of Congress.